Waste, Climate and Health

Thought Pieces

Author: Ceris Turner-Bailes

Published: 17 September 2021

At the same time as reducing climate emissions, waste management services reduce the spread of disease and the burden of poor health on vulnerable populations. Ceris Turner-Bailes, WasteAid’s CEO, shares the organisation’s perspective on how waste, climate and health are linked together.

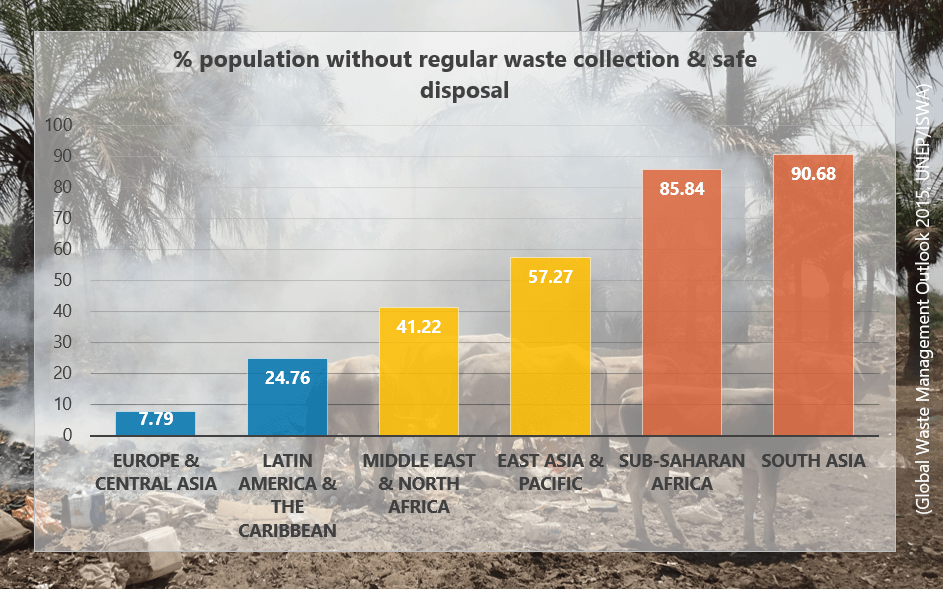

A regular waste collection and safe disposal service is a luxury that many people in the world do not have, with 1 in 3 people globally going without. The Sustainable Development Goals cannot be met without urgent attention to global waste management and its associated impacts on public health.

Where there is no waste management, residents and business owners have to dump or burn their waste. Accumulated waste and blocked drains encourage mosquitoes to breed, resulting in the spread of malaria, dengue fever and yellow fever. Blocked drains also cause severe flooding, leading to a spread of water-borne diseases, and the loss of lives and property.

Each year approximately 9 million people die of diseases linked to mismanagement of waste and pollutants, 20 times more than die from malaria[i].

Open burning of waste

Uncontrolled burning of household waste causes an extra 270,000 premature deaths every year around the world[ii]. Burning waste emits fine particles, dioxins, volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, and polychlorinated biphenyls, linked to heart disease, cancer, skin diseases, asthma, and respiratory illnesses[iii].

Eggs from chickens that forage around waste yards and plastic burning sites have been found to contain high levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs)[iv], which have been linked to cancers, neurological disorders, immune suppression, reproductive disorders and diabetes, and are particularly harmful to infants, children, women, and under-nourished populations[v].

For children, the health risks posed by unmanaged waste and poor sanitation are particularly harmful[vi]. Impacts include nutritional malabsorption[vii], diarrhoea, respiratory illness, stunting and educational underachievement.

Since domestic waste disposal is usually the responsibility of young women in a household, the risks from open burning are multigenerational. Unborn babies and small infants are particularly susceptible to the impacts of localised pollution, compounding barriers to communities improving health outcomes and educational attainment.

Open dumping of waste

Waste in the environment can contaminate water supplies, harming people, livestock and crops. It eventually finds its way into streams, rivers and the sea, causing serious ecological and public health problems. Fish, livestock and other animals that eat waste often become ill, either from disease or from stomachs full of plastic[viii]. Flies, dogs, rats and snakes are attracted to waste heaps, posing further risk to people nearby.

When rainwater washes through waste it can pollute surface and groundwater. Many dumpsites are on the coast or riverbanks, contaminating the global food chain.

Dumpsites put entire populations at significant risk from negative health impacts. It is estimated that 40% of the world’s waste is disposed of at informal dumpsites, most of which are completely unmanaged[ix]. Frequent fires pollute the air with unpleasant black smoke and odour. The smoke can cause breathing difficulties and harm the skin and eyes of those nearby. It can be very challenging to extinguish a fire on an open dumpsite, with limited access to water and the fire reaching far below the surface.

Uncontrolled dumpsites, and in particular the mixing of hazardous and other wastes, can cause disease in neighbouring settlements as well as among waste workers. Dumpsites are a greater health risk for the millions that live near to them than malaria[x].

Scavenging from dumpsites is a very risky business, with constant threats of injury, vermin, disease, and most worryingly, being buried alive in falling mountains of waste. Mixed waste on dumpsites has little value, and sorting mixed waste can be a dirty and dangerous task. Scavenging and contact with waste can lead to increased cases of dysentery, diarrhoea and cholera. Sharp items such as broken glass or needles are harmful underfoot, and open wounds are easily infected.

Legacy issues

Closed dumpsites remain contaminated and hazardous places for a long time, and continue to pollute the local air, land and water. Globally, the release of methane and black carbon (in smoke) from uncontrolled dumpsites is accelerating climate change, which in turn exacerbates drought, famine and the spread of disease.

We need to consider very carefully the legacy we are leaving for future generations. Concerns about the climate are front-of-mind, particularly in the lead up to COP26. The associated burdens of mismanaged waste, which are increasing on a daily basis, need to be recognised fully and addressed with urgency.

WasteAid is working with partners to attract funding, develop guidance, and promote waste management as a public health imperative. If you feel you can contribute towards our mission, please get in touch.

References

[i] UNEP (2015) Pollution is the largest cause of death in the world, SDG fact sheet; World Health Organisation (2017) Global Health Observatory data on malaria mortality.

[ii] Kodros JK et al (2016) Global burden of mortalities due to chronic exposure to ambient PM2.5 from open combustion of domestic waste, Environ. Res. Lett. 11 124022.

[iii] Human Rights Watch (2017) The health risks of burning waste in the Lebanon https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/12/01/if-youre-inhaling-your-death/health-risks-burning-waste-lebanon

[iv] Petrlik, J., Ochieng Ochola, G. and Mng’anya, S. (2020) Plastic Waste Poisons the Food Chain in Kenya and Tanzania (ARNIKA and IPEN)

[v] IPEN (229) POPs at a glance. https://ipen.org/toxic-priorities/what-are-pops

[vi] UNHABITAT (2010) Solid Waste Management in the World’s Cities; UNHABITAT (2012) Recycling and disposal of municipal solid waste in low and middle-income countries; Humphrey, JH (2009) Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets, and handwashing, The Lancet, 374(9694):1032-1035; UNICEF and SHARE (2017) The impact of poor sanitation on nutrition; Boadi KO and Kuitunen M (2005) Environmental and health impacts of household solid waste handling and disposal practices in third world cities: the case of the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana, Journal of Environ Health, 68(4):32-6.

[vii] Nutritional malabsorption is caused by environmental enteropathy, an intestinal inflammation that prevents the absorption of nutrients from food and oral vaccines. The implication of this is that children growing up around dumped and burning waste end up with malnutrition, even if they are eating regular and decent meals.

[viii] Various sources, including Tiruneh R, Yesuwork H (2010) Occurrence of rumen foreign bodies in sheep and goats slaughtered at the Addis Ababa Municipality Abattoir, Ethiopian Veterinary Journal Vol 14, No 1; and Mushongal et al (2015) Investigations of foreign bodies in the fore-stomach of cattle at Ngoma Slaughterhouse, Rwanda J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. Vol 86, No 11 Pretoria.

[ix] ISWA (2016) A Roadmap for Closing Waste Dumpsites, The World’s Most Polluted Places

[x] K. Chatham-Stephens et al (2013) Burden of disease from toxic waste sites in India, Indonesia and the Philippines in 2010, Environmental Health Perspectives.